Threshing: how grain and straw were separated at harvest

What threshing was; the threshing machine/thresher, how it worked and was powered; traction engine; clothes to protect workers from dust and vermin; timing.

____

by Neil Cryer who helped, as a boy, with bringing in the harvest

Ears, grain, straw, chaff and threshing

All cereal crops grow as tall stems with the grain in what are known as 'ears' at the top. These ears are complex structures holding a dozen or more ripe grains which need to be separated from the rest of the plant at harvesting. The separation process, known as threshing, is basically a matter of roughly knocking the harvested crop around to make the small grains drop. The bitty remains of the ears are known as chaff.

Ears of wheat ready for harvest

Corn and wheat

The most commonly grown cereal crop in the UK is wheat, but there can be confusion between it and corn. In the UK corn is generally used to mean wheat, and we speak of cornfields even where the crop is wheat. In other countries corn can mean maize.

Before the 1940s the process of separating out the grain was done by what was known as a threshing machine or just a thresher. Today, threshing is part of the complete harvesting process and is done by what is called a combine harvester.

The threshing machine/thresher

How grain is separated and captured

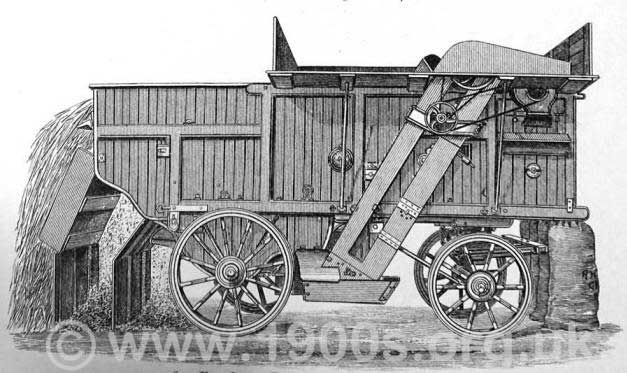

Essential parts of a threshing machine/thresher showing its operation

The crop, is fed into the machine at the top as shown in the above sketch. Inside there is a fast rotating drum which is part surrounded by a section of a larger drum. Both the drum and the surrounding section have bars on them designed to batter the crop quite hard. The rough treatment releases the grain which drops out through the holes in the lower section. It is then collected in sacks. What remains is straw and is ejected.

Drawing from an encyclopaedia printed in the late 19th Century. It shows the straw being ejected - top left, and the separated grain dropping into sacks - bottom right. What it does not show is a man standing on top feeding the crop in. Interestingly the encyclopaedia labelled the sketch as a thrasher not a thresher.

Placement

The thresher was placed as close as possible to where the crop had been stacked after cutting. In fact the original siting of the stack had to allow for all the placing of the equipment, usually near a field gate.

A traction engine for power

The threshing machine was powered by a belt from a traction engine. The belt was long and it whirled round at head height, so everyone was expected to keep clear. There were no health and safety precautions.

Traction engine powering the thresher which is off-screen on the left. The moving belt is easier to see in the next photograph. Photographed at a 21st century country show.

Moving belt connecting the thresher to a traction engine. Photographed at a 21st century country show.

How the grain was separated from the chaff

The loose grain had to be separated from the chaff which was generally less dense. This separation was done inside the thresher by a combination of a grid which allowed the grain to drop through and a fan which blew the chaff elsewhere. The grain then fell down a shoot into waiting sacks, suspended at one end of the machine as seen in the picture below.

Grain being delivered into sacks at one end of a threshing machine. Photographed at a 21st century country show.

The remaining straw was ejected from the other end of the machine. The ejected straw was frequently caught by an escalator which fed it to a new stack or left on the ground to be pitched onto a cart and carried away for various uses or storing.

Today the straw normally goes to a bailer.

Straw being delivered onto the ground at the other end of an old threshing machine. Detail of an old photo supplied by Send and Ripley History Society. Note the solid tyres.

Fun for children

contributed by Dick Hibberd, recollections

Threshing was a source of great fun with the traction engine's smoking chimney, puffing pistons and majestic drive wheel linked via a huge belt to the threshing machine. It was even bigger than the traction engine.

Timing

Threshing was often sometime after cutting. Because threshing machines were so expensive, few farmers could afford to buy their own. So a single machine was hired out locally from farm to farm, which meant that the time of a farm's use depended on both the weather and the availability of the machine.

Fortunately because the need for grain was not confined to harvest time, threshing could take place at any time of the year, particularly at less busy times. This meant that the sheaves had to be stored in stacks or barns. Then they were processed inside the barns, which was excessively dusty.

Dust and vermin and how workers coped

The whole process was a dirty, dusty business, particularly when it took place inside a barn. So men wore clothes accordingly. Hats, in particular, were considered essential. Wide brimmed hats seemed preferable to the standard cloth hats of the time.

The vermin in the stack waiting to be processed

contributed by Dick Hibberd, recollections

I was one of a number of young lads armed with clubs surrounding the stack as its contents were removed for threshing. It was our job to eradicate any vermin as they left their diminishing larder/home. There were also elderly men with Jack Russell terriers.

The frequency of escaping mice and rats increased as the stack grew lower.

The Jack Russells were very efficient little killers. They just grabbed a mouse or rat by the scruff of its neck, shook it violently, dropped it and moved on to the next one. The dropped animal never moved again.

When threshing took place from a stack in a field, there was another essential item of clothing as explained in the following box.

Workers' trousers

contributed by Dick Hibberd, recollections

The men that I saw dismantling the stack tied a cord around their trouser legs just below the knee. I was uncertain why until I saw the less than graceful dance that one of the farmhands performed. He had not had time to tie up his trousers, and a mouse had run up one trouser leg and took its time before running down the other. The man's gyrations, hopping, skipping and jumping were most entertaining. We lads all wore short trousers and were perhaps a little more agile, so were not really vulnerable.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.