The CC41 utility mark in WW2

The CC41 utility mark appeared on what were known as 'Utility' goods, which were manufactured to meet the UK Government's austerity requirements in WW2. Utility goods were basic and functional with the huge advantage of being free of purchase tax. This page explains why the mark was needed and its design; and describes some typical utility goods and legal and illegal ways of obtaining non-utility goods.

____

By the webmaster: her early recollections, discussions with others who lived at the time and further research

Utility goods and the utility mark

During the austerity in and after WW2, the Government decreed exactly what raw materials could and could not be used in the manufacture of goods. Goods which met the provisions were described as 'utility' and were marked with what was called the 'utility mark'. These goods were basic and functional with the huge advantage that they were purchase tax-free. Non-utility goods could be sold, but were increasingly scarce and subject to a purchase tax which made them less popular.

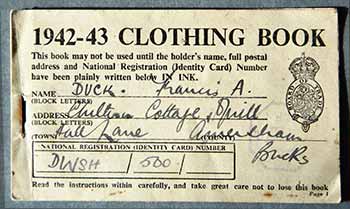

Utility goods, like so much else, were rationed at a certain number of coupons or points from customers' clothing books.

Clothing ration book, 1942-43

Like everything else, utility goods almost always still had to be queued for.

The utility mark, CC41: design and meaning

I saw a lot of the utility mark when I was a child in the 1940s. It was in the design of the characters CC41, but it was only ever called 'the utility mark'. In fact, it was only some years after the war ended that I found out that the design actually portrayed CC41.

The 41 - strictly 1941 - was the year that the relevant Government discussions took place, following the introduction of clothes rationing early that year. The CC must have stood for Civilian Clothing as there was then a Director of Civilian Clothing at the Board of Trade, and clothing was the initial stimulus for utility goods. I also assume that the design was chosen to be easily recognisable, but not to shout its meaning of austerity, rationing and lack of choice while the public was already suffering so much in the war. If this was the intention, it certainly succeeded.

In the remaining ten years of the mark's use, the 41 date was not updated and the CC also remained although the utility requirement was extended to goods other than clothing, like shoes and furniture.

Examples of utility marks and how they were attached

How utility marks were attached to goods depended on the surface. The first of the following photos shows it as cloth, neatly sewn onto knitwear, whereas the second and third photos show it stamped onto items which would be next to the skin where it needed to be less bulky, more flexible and non-itchy. When utility requirements were extended to furniture, the mark was engraved.

The utility mark sewn onto knitwear

The utility mark stamped onto socks

Utility mark stamped onto a warm, long-sleeved vest

The utility mark sewn onto a liberty bodice

The liberty bodice

Liberty bodices were the early-mid 20th Century equivalent of vests for girls. They were made of stout woollen fabric and did up like cardigans. Note the heavy strips designed to flatten developing chests and the rubber buttons to go through a mangle on washday without breaking.

Public reaction to utility

Not surprisingly, the public's reaction to utility goods being imposed on them was negative because of the lack of perceived choice and quality. However this changed. As utility goods came onto the market, the public was surprised at their functionality and adequate quality. Both can be understood from the following photos of a man's utility winter coat, generally known as an overcoat.

Front of a man's utility overcoat

Back of a man's utility overcoat

The quality is outstanding. Remember that this was before the man-made fibres of today could bulk out coat linings to keep in body warmth. This coat is made of a thick woollen fabric in a herring-bone pattern and is lined with a quality fabric for extra warmth. There are pockets and matching buttons, and, for even additional warmth, is double-breasted and long enough to cover a man's knees. Interestingly, several sources state that austerity required fabric to be saved by jackets having to be single breasted and there being no turn-ups to men's trousers. I can't comment on the trouser turn-ups, but the evidence of this set of photos shows that at least some double-breasted jackets were allowed.

Detail of the thick woollen quality fabric

Utility mark sewn into the lining. Note how untidily it is sewn compared with on the more visible knitwear in the above photo.

These coat photos are courtesy of Graham Prescott

Non-utility goods

Alternatives to utility goods were available, but not necessarily legally.

Pre-war goods

Goods that were manufactured before the utility restrictions and still in the shops were still available to buy, although they were officially rationed. However, it was widely known that they were under the counter for special customers and sold at inflated prices. Furthermore, they didn't last long in the shops. For example, I was born in 1939, five months before the war started and had shop-bought toys presumably given as birth presents by aunts, uncles and grandparents, but my cousin, born two years into the war tells me that he had no shop-bought toys.

'Barrow Boys: discount street traders

Although I never saw any shops or market stalls selling cut-price or rationed goods during the years of rationing and austerity of the war, what I do clearly remember are what was known as barrow boys. They sold goods from large barrows on wheels. The following photo gives the idea, although what barrow boys sold was not generally the fruit and veg shown in the photo. It was such things as second-hand clothes, and ornaments and tools. Where they got their goods from is anyone's guess. 'Falling off a lorry' was the generally accepted term, although I cannot vouch for how true this was.

The point is that barrow boys did sell goods which were probably questionably illegal in some way.

A barrow boy being accosted by a policeman

Barrow boys frequented busy streets. They knew that what they were doing was probably on a questionable side of the law, so were always on the look-out for policemen. If they saw one coming, they would trundle their barrow away as quickly as possible. They normally worked from somewhere that had rapid escape alleyways.

Somehow, after the end of the war, ordinary people didn't seem to mind using barrow boys, although they would never have broken the laws on rationing while the war was on. I remember my mother buying something from one of them along London's Oxford Street. She gave him a pound note but he instantly rushed away pushing his barrow as fast as he could. She was left standing there without her change and with amazement all over her face. She found out later that he had seen a policeman coming. He shouted back at her, "Round the corner!" and when she followed him there, he gave her the change. So he hadn't meant to defraud her, only to avoid the policeman. Actually the policeman must have seen what was happening, but chose to turn a blind eye.

Barrow boys did a good trade and were well-patronised by the public.

Cottage industries and scarce goods

As explained on the page about the Government policy on rationing, rationing was set up so there were fair shares of what was available for all. In other words, when goods and foodstuffs were enough to go round, however little there was, they were rationed. If there was not enough for everyone, whatever was available was not rationed, but available on a 'first come, first served' basis. Cottage industries were good examples, as there was no way they could share nationally, say, a crop of apples. So their goods were off-ration. If word got around that some such goods were available, people would cycle miles to find them.

Gifts from American soldiers

Young British women who befriended American soldiers would get gifts from them like nylon stockings, which were simply unavailable in our British shops.

Living as I did in Edgware, I never saw an American soldier during the war, but I knew that they were regarded as having no shortages at all. (This still puzzles me, as presumably the merchant seamen who brought in their luxuries were risking their lives to do so. Or perhaps the goods were flown in.) My cousin did see American soldiers and got chewing gum from them.

The black market

The black market was an illegal, secretive and generally despised trade which enabled people to buy what they wanted off-ration at exorbitant prices. It has its own page.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.