GMT, BST, WW2 Double Summer Time and the 'right' time

GMT, BST and Double Summer Time are abbreviations for the UK's systems for agreeing the time, and this was as true before the digital era as it is today. Then people had to rely on timepieces that lost or gained, with obvious problems. This page starts with a brief explanation of GMT, BST and Double Summer Time and continues with what it was like to live with these systems in the predigital area and how people coped with finding out the 'right' time.

____

By the webmaster based on personal experience and further research

The background

The background to this page is that each town and city in the past set its own local time based on the position of the sun. This meant that different regions of the country and the world had different times which was little problem until travel across between regions on the railways was becoming a serious timetable problem.

My great grandmother is on record for sending her granddaughter to the foreman of a factory to ask the time, whereupon he took out his pocket watch and answered, "If your grandmother wants to catch a train, I can't say, but tell her that it is about ...."

In fact, similar problems were worldwide, and In 1884, an international conference established large zones which would agree to using identical times. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was the standard for the UK.

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) and British Summer Time (BST)

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the time as measured with great precision by the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, based on the movement of the Sun. So, at Greenwich, the brightest time of day is designated as 12.00 noon for the whole of the UK.

In order to make the best use of daylight, the UK like many other countries has two time zones. During the dark days of winter it is Greenwith Mean Time, but in the long daylight hours of summer it is British Summer Time (BST). Then clocks go forward one hour, making the brightest time of day 1pm or 1300 hours. This makes a lot of sense as daylight extends more into the evening when people want to be outside. The fact that it is darker in the mornings doesn't matter because there are still enough hours of daylight for most people to get up in daylight.

BST normally starts at 1am on the last Sunday of March and continues until 1am on the last Sunday of October when clocks are set back to Greenwich Mean Time - although the Government can vary these dates slightly to support trade with overseas.

In other countries the change in time for summer is called Daylight Saving Time.

Embarrassment when the summer time change was missed

When I was a young child at school in the 1940s, there was always fun twice a year when classmates turned up for school at the wrong time. This happened when their parents missed changing from GMT to BST and vice versa. Clocks and watches did not change automatically as they do today with digital timepieces.

Double Summer Time to save fuel

During the austerity of WW2, Double Summer Time was introduced in the UK as a way of saving fuel. This saw clocks being put forward two hours ahead of GMT.

Double Summer Time was triggered on the last Sunday of October in 1940 when the clocks were not put back from Summer Time to Greenwich Mean Time. The result was that Summer Time continued throughout the Winter of 1940/41. On the last Sunday of March in 1941, the clocks were put forward an extra one hour, effectively putting the country two hours ahead of GMT. This meant that dark evenings were two hours shorter, so the time for which heating was required was also two hours shorter, thus saving on fuel. The delayed darkness in the evenings also meant that people had more time to get back home before the blackout.

WW2 Double Summer Time ended in the Autumn of 1945 when clocks were set back to the previous cycle of Greenwich Mean Time over winter and British Summer Time in the Summer.

The end of WW2 was not the end of the meddling with GMT and BST. In February 1968 the government introduced an experiment whereby clocks were set permanently one hour ahead of BST. The experiment was abandoned and clocks went back to standard Summer Time in 1972.

Advantages and criticisms of Double Summer Time

Double Summer Time in WW2 certainly did save fuel, and peole liked the shorter dark evenings and having to put up their blackout an hour later. However, after the end of WW2, there was no need for blackout, but there was the continuing advantage of saving fuel. Another advantage was that Double Summer Time resulted in fewer accidents in the lighter evenings. Unsurprisingly though, there was a slight increase in accidents in the darker mornings.

Double Summer Time was particularly unpopular in Scotland where winter days have shorter daylight than in the South, and the experiment resulted in school children going to school in the dark.

What answer is expected from the question, "What's the time?"

When asked the question, "What's the time?", people in general don't give a thought to whether they are in GMT, BST or Double Summer Time. They want to know what the time is according to the time that organisations, public transport and meetings etc are working by, that is the time that is currently standard throughout the country or their time zone. In today's digital age, people generally agree on what the right time is because digital timepieces are accurate to the second and keep perfect time.

The same was not true before the digital age.

The 'right time' in the predigital era

Before digital timepieces, knowing and agreeing on 'the time' was normally a hit-and-miss affair, as it was normal for clocks and watches to lose or gain slightly. In fact, it was quite common to be stopped in the street and asked, "Do you have the right time please?". The stress was on 'right' because the person asking probably knew that it was nearly time for the next meal or a particular bus to arrive. They just wanted certainty.

Setting the 'right' time

In my family home in the 1940s, we checked for the right time once a week and reset our timepieces accordingly. There were three ways to do it.

The speaking clock, dialling TIM for the 'right' time

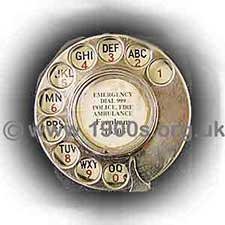

Dial of an old phone showing letters as well as numbers

The Speaking Clock was a service introduced by a number of phone companies in July 1936. Then, all phones had a dial system with numbers and letters as shown in the picture above. To 'dial' a number, the user put a finger in one of the holes, pulled to rotate the dial clockwise to the stop shown in the picture and let go. This was called dialing. For the speaking clock, we had to 'dial' T followed by I followed by M. This was called dialling TIM.

Phoning TIM was often the task of a young child, as it was something a child could easily manage and would enjoy doing. At the end of the phone, a voice would say, "At the third stroke, it will be 11.23 and 6 seconds (or whatever)". This was followed by three beeps which the talking clock referred to as strokes. Then the message was repeated as often as one cared to stay on the phone, with the time accordingly being updated. Not that anyone stayed on the phone for long, because telephone calls were expensive in real terms.

I assume that the voice was recorded. If it were not, it must have been the most monotonous job possible.

Phoning TIM had the advantages that it was accurate to the second and could be done at a time of one's convenience, but phone calls did cost, and by no means every household was on the phone. (We were for my father's work.)

Big Ben's chimes from the radio

Another way of finding the right time was from the radio - then called the 'wireless'.

On December 31st 1923 the BBC heralded the New Year by broadcasting the chimes of Big Ben, the well-known London clock, to herald the New Year. From then onwards, the chimes from Big Ben were broadcast immediately before the news. The number of strikes marked the hour, one strike for one o'clock, two for two o'clock etc. Once it got to 12 o'clock we never bothered with which of the twelve chimes marked the exact hour. This was accurate to the minute.

Big Ben with its large clock set up high to be read from a distance

Big Ben's chimes were recorded during World War Two in case the clock was put out of action in the blitz, as it was important for morale that it continued to be broadcast.

Also, most programmes were broadcast at known times but the timing could be out by one or two minutes.

The 'pips' for the 'right' time from the radio

The Greenwich Time Signal (GTS), frequently known as the 'pips', was a short set of six tones broadcast at one-second intervals by many BBC Radio stations to mark the hour. The start of the last pip represented the precise start of the hour.

The pips were introduced in 1924. Today, the accuracy of time via the radio can be affected by modern digital broadcasting. As I write, the broadcast of the pips on BBC FM comes a number of seconds before digital radios sound them. If you miss the pips on your FM broadcast, should you want to, you can set your clock a few seconds slow by listening to the digital radio.

The procedure for setting timepieces to the right time depended on the type of timepiece, as explained on the clocks, pocket watches and wrist watches pages.

Importance of shop clocks and church tower clocks

Clocks and watches are cheap in today's terms because they are digital. Before then, they were expensive. Ordinary people may have had one clock in the house, but few owned their own watches. My mother was given a wrist watch by the family clubbing together for her 21st birthday. Men's pocket watches were a status symbol.

So how did ordinary people know the time? The answer was from the large church clock on the clock towers of the numerous local churches. These clocks were placed up high so as to be seen from a distance. I am told that when my grandmother was a young woman, she regularly went into the back yard to check the time from the church clock.

Large clock positioned up high up on a church tower to be read from a distance

Shop owners regarded it as their duty to display a clock inside or outside their shops.

The accuracy of these clocks was unreliable, but people knew that and would speak of the time being 'about' whatever. They knew nothing different and accepted things as they were.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.