Crank phones also known as wind up phones and magneto phones

Crank phones, magneto phones and windup phones are all names for old telephones which worked on batteries and had to be wound up by hand using a handle on the side of the phone. This generated electricity to charge the batteries. The page describes the phones and how they worked. It goes on to explain how they were used to make a call, based on the personal experiences of a former user. Well illustrated.

____

By the webmaster, based on contributions from a website visitor with additional research

If people from today could go back in time to visit a home with a very early telephone, they could well be puzzled by seeing a winding handle on the side. Closer inspection would also reveal large batteries nearby.

Such telephones were known as 'wind-up' telephones, 'crank' telephones or 'magneto' telephones.

The names magneto phone and crank phone

Turning the handle on the side of these phones caused a magnet and coil system to generate electricity. The electricity then caused a bell to ring back at the exchange. Thus turning or cranking the handle was the action required to alert the operator. The name 'magneto' came from the magnets which were part of the electrics.

The name crank phone comes from crank meaning to turn or rotate something using a handle or lever.

Wind-up/crank phones were most common in small communities in rural areas, particularly where there was no electricity.

To avoid repetition, I shall refer to them as wind-up phones, but first how they got these names.

contributed by NR (name supplied)

Our family had a wind-up phone - and just to show how small and isolated our village was, the operator was also the post mistress who also ran the local boot and shoe shop. Her husband was a farmer and the local undertaker, and if she was busy and he was around, he would occasionally step in for her. At the time we did not have electricity. Even the radio (known as the wireless) had to have a dry battery and a wet rechargeable battery which had to be taken to the nearest town for charging.

As wind up phones were so early, you may be surprised not to see a candlestick version. The reason is that candlestick phones got their name from the shape of the stand on which the mouthpiece was mounted, the earpiece being separate. With these types of phone there was no room for additional mechanisms. So where a windup phone was needed, a largish wall-mounted wooden box housed the mechanism and served to mount the winding handle and the cradle for the earpiece. The box had an open top so as not to muffle the sound of the ringer. No photo yet, but the following stylised sketch should show the idea.

Wall mounted windup phone

Why the batteries?

The power to run modern telephones comes from the telephone exchange, and the same was true with the newer manual exchanges, old as they must seem to us now. However the small, older exchanges, mostly in rural areas, did not supply the power to run the phones or, if they did, this power was only short range. So batteries were needed.

Batteries for a wind-up phon

There were two batteries which provided 3 volts total, and they could last a year or more.

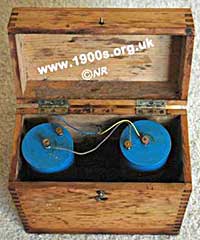

Battery box, now stripped of its original varnish.

Open battery box, showing batteries,

These photos and the one at the top of the page are courtesy of NR.

The batteries were normally kept under a telephone table in a beautifully made, varnished wooden box which came with the phone.

Why the handle?

There was no dial on these early phones. So someone wanting to make a call had to start by alerting the operator at the exchange. This was done by turning the handle on the phone to ring a bell at the exchange.

Handle of a wind-up phone, courtesy of NR.

How to make a call on a wind-up phone

contributed by NR (name supplied)

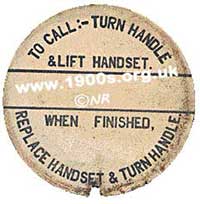

To start a call, we turned the handle to attract the attention of the operator and lifted the handset. If the operator's phone was in use, the handle was hard to turn and we had to try again later.

Label on a wind-up phone showing instructions for making a call, courtesy of NR

There could be quite a delay in the operator answering because, remember, our operator was also the local post mistress and who also ran the local boot and shoe shop.

The operator knew that someone was calling because the bell sounded and she knew which line it was because each subscriber's line had a little shutter on a small window, and this would fall open ready for a connection to be plugged in.

Operator's telephone swtichboard

When the operator answered we heard her ask for the number we wanted, which of course we said.

For a local number the operator would make the connection directly, by plugging our line into that of the number we wanted. If the call was answered, she would say, "You're through"; and if the call was not answered, she would apologise and say that the person being called was not at home.

Our operator knew everyone on her exchange by name and number because there were so few subscribers. At first there were only eight. The post office itself was number one and the local police station was number two. My grandparents' home was number three and we were number four. The numbers were allocated in the order in which householders subscribed, and they were connected in that order. Another number was for the next exchange which was used for routing calls to remote exchanges.

If the requested number was not local, the operator would call the next exchange which might need to connect to one or more further exchanges.

At the end of our call, we would replace the phone on the cradle and turn the handle to let the operator know that the call was finished and could be disconnected. On disconnection the shutter at the exchange would close.

When making a call through any manual exchange, callers had to remember that operators could be listening in. So nothing risqué could be talked about. Operators on small manual exchanges often knew everyone's business.

Costs of making a call

contributed by NR (name supplied)

Call time was charged in three-minute units. I seem to remember that a local call to someone on the same exchange was only 2d (two old pennies).

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.