How shopkeepers set prices with pre-decimal money

Pricing goods to make them appear cheaper at first sight probably goes back for as long as people used money to trade. This page gives examples from 20th Century Britain, from before and after the decimal changeover.

____

By the webmaster, based on personal recollections and firsthand contributions

Pricing goods to make them seem cheaper

The following example comes from the early years of the 20th Century when the humble farthing was regarded as valuable.

extracted from the memoirs of Florence Clarke (1906-2002)

Farthings [quarters of old pennies] were used a lot, and everyday goods were usually priced to a farthing less than the next penny up, presumably to make them look cheaper at first glance.

For example, something that effectively cost three pennies was priced at two pennies and three farthings - 2¾d. This practice was so common that that, for example, if something cost one penny and three farthings, i.e. 1¾d, everyone said "a penny three".

Pricing policy and inflation

In later years, as inflation increased prices and farthings were withdrawn, shopkeepers still used the same pricing policy to make goods look cheaper at first glance. In pre-decimal currency goods might be priced at, for example, nine shillings and eleven pence, i.e. 9/11 rather than 10/- rather than ten shillings. After decimalisation goods tended to be priced at one new penny less than the next pound, i.e. £5.99 rather than £6.

Farthings in pricing policy mid-20th century

contributed by Eric Cowley, comment and recollection

In the 1940s and 1950s farthings had no significant buying power. They were minted right up to 1956 and decreed no longer legal tender from 1960. During this time, shopkeepers found them annoyingly fiddly. In the early 1950s, for example, I used to buy a small loaf of bread from the local bakers which I had sliced for 4¼d (fourpence-farthing). I usually carried a few farthings in my pocket for such purchases but if I tendered 4½d (fourpence-ha'penny), I would get disgusted looks if I kept my hand out waiting for the change.

The shortage of farthing coins mid-20th century

contributed by Stephen Drury recollections

Although farthing coins were still legal tender in my childhood in Ireland, there must have been a shortage of them in circulation, because some shops used pieces of card, printed with some suitable wording to represent the farthing. So you might receive change that included a piece of card and then you could use that card towards payment for goods the next time you shopped there. Of course, they were only valid in that particular shop.

Price cards in shops

Because shops needed to attract customers who might otherwise just be passing by, they displayed prices on the goods in their windows.

Similarly once customers were inside the shop for one purchase, shopkeepers needed to attract them to buy other things by putting the prices on their counter goods.

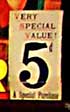

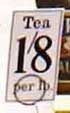

So price-display cards were common. They were quite large - perhaps of a size between that of a child's and an adult's hand. The following images show samples of price-display cards as they appeared in the early to mid-20th century. I discovered them in a range of museums which unfortunately don't show the pricing policy explained above.

See the separate page on how these prices would have been pronounced.

A hard way for children to learn about pricing policy

contributed by Paul Mc Cann, experience

One day in primary school a teacher was wiseing us up to shop keepers pricing things at the nearest pound less a penny. On the way home from school a friend and I spotted a window where everything was priced this way. We were laughing and pointing the price tickets out to each other when a policeman gave us a clip around the ears.

"That's no window for ye to be looking in", he said.

We had no idea what he meant. It was a window full of women's underwear! Being less than 10 years old, we were innocents.

Incidentally we thought nothing of being clipped round the ears by a policeman. This was considered quite acceptable from authority figures in the early 1950s.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.